Pisgah Presbyterian Church, Founded 1784, Woodford County, Kentucky.

Pisgah Presbyterian Church, Founded 1784, Woodford County, Kentucky.

The beautiful church and cemetery of Pisgah in rural Woodford County was alive with green grass and spring violets when Ritchey and I visited in April of 2014. Several Revolutionary War veterans repose there, many from Augusta County, Virginia. The one stone that brought tears to my eyes was that of William Kinkead. His stone bears a marker for his children and wife. Eleanor Guy Kinkead and three of her children were taken by Indians April 14, 1764, while William worked in the fields. The two eldest children died while in captivity, the youngest of the three survived, and the child Eleanor was carrying was born during that time.

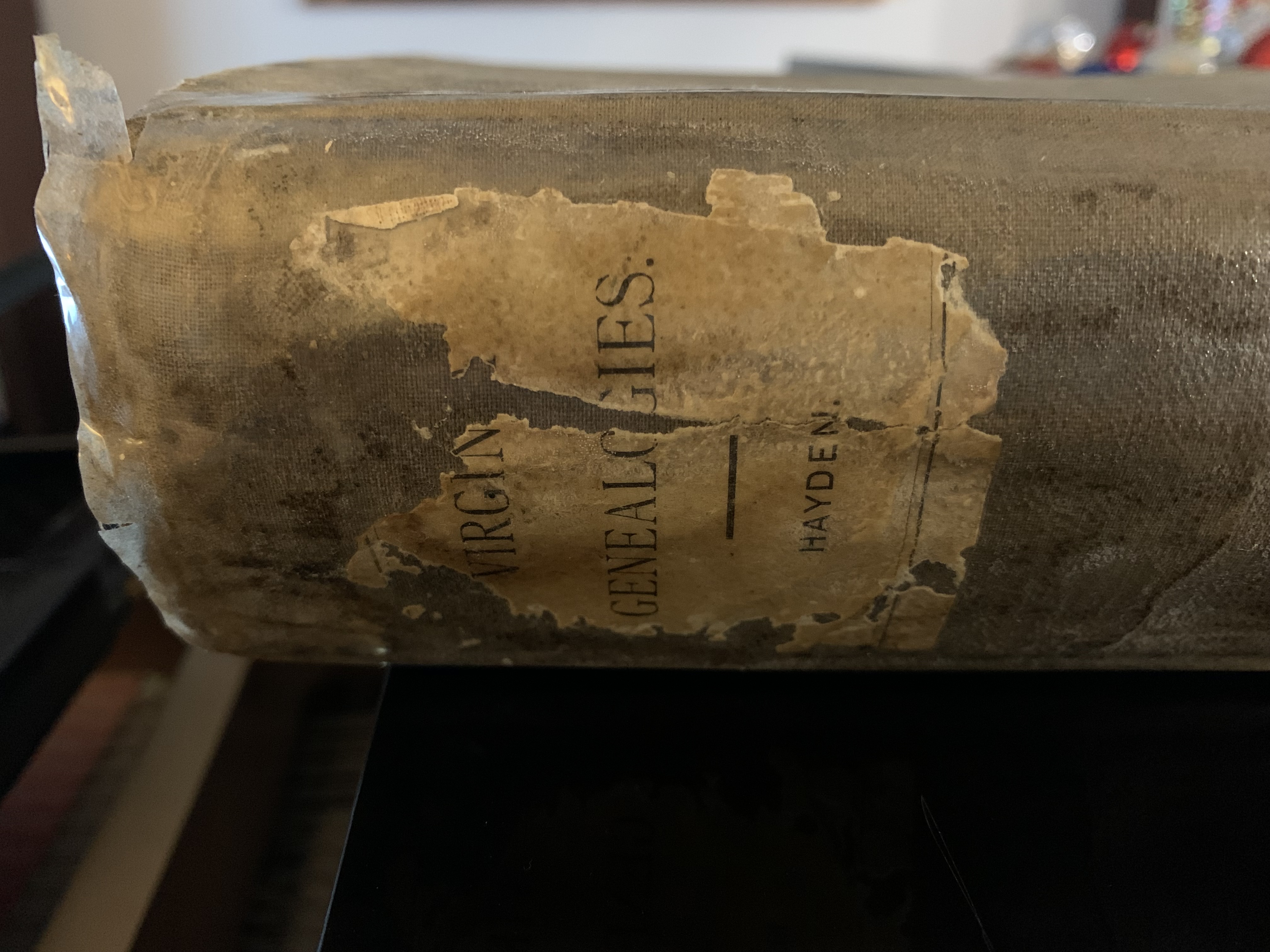

Today I found the following information on William and Eleanor, a letter written by their grandson John, telling about his mother and sibling’s capture from their home in Augusta County, Virginia. This was taken from Appendix C of Genealogies of Kentucky Families from the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society O-Y, 1981. The Families Kinkead, Stephenson, Garrett, Martin, and Dunlap, excerpted from Historic Meeting at Pisgah Church, by Laura Kinkead Walton, from Vol. 37, October 1939, pages 283-321. Just the thought of what happened makes me terribly sad, but to read the details of the letter bring it vividly alive.

Today I found the following information on William and Eleanor, a letter written by their grandson John, telling about his mother and sibling’s capture from their home in Augusta County, Virginia. This was taken from Appendix C of Genealogies of Kentucky Families from the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society O-Y, 1981. The Families Kinkead, Stephenson, Garrett, Martin, and Dunlap, excerpted from Historic Meeting at Pisgah Church, by Laura Kinkead Walton, from Vol. 37, October 1939, pages 283-321. Just the thought of what happened makes me terribly sad, but to read the details of the letter bring it vividly alive.

William Kincaid, the eldest son of Thomas Kincaid and Margaret Lockhart, was born at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, January 9, 1739, and died in Woodford County, Kentucky, May 30, 1820. He moved to Augusta County, Virginia, with his parents and remained there until after the Revolutionary War. On November 30, 1756, he married Eleanor Guy.

Eleanor Guy Kincaid was a woman of great courage, prepared for the rigors of pioneer life. She was of the same Scotch-Irish ancestry. Her maternal great-grandfather had fought in the siege of Londonderry and what was more important her great-grandmother had lived through it, and she had been brought up on tales of its horrors. In her later years she told these stories to her grandchildren, rivaling Macaulay in the vividness of her description of the ferocity of those times. She, like her husband, had a background of strong religious belief, for which men had suffered and died, and her faith was tried to the uttermost in the savage adventure that befell her.

In a letter from her grandson, to his son (my great uncle), the story of her capture and escape from the Indians is told far better than I can tell it and I give it in his own words.

Cane Spring, April 20, 1847

Dear Blackburn,

You request that I should give you some of your great-grandmother’s early history. I am at a loss where you wish me to begin, but I suppose I may go back as far as I have any dates. She was born August 17, 1740. Was married to your grandfather November 30, 1756. Was taken captive by the Indians April 14, 1764, from Augusta County, Virginia, twenty miles from Staunton, on the road to Warm Springs. She had, when she was taken, three children, the eldest a daughter, seven years old, the second a son four years old, the youngest, your Aunt Hamilton, two years old.

When the Indians came to the house, your grandfather had but a short time left. He had eaten his dinner and gone to the fields out of sight of the house, to plough. Your grandmother was sitting just inside the door spinning, the children were playing at the door, when, suddenly, they screamed, as though alarmed, and before she had time to rise, an Indian jumped in at the door, there were five of them four men and a boy. They immediately went to packing up the clothing; they cut open the beds, throwing out feathers. Several persons had brought their clothing there, believing it to be the most secure place in the neighborhood, and intending to come and build a fort there. They took all their clothing. There were two guns in the house, and a new saddle; they took all. She said it was astonishing the load that they carried. The Indians had never come as early in the season before, and their visit was utterly unlooked for at the time.

Your grandfather did not return to the house until night. You may imagine his feelings when he came and found things as they were. He immediately turned out to raise a company to pursue them and started the next morning and followed them for two or three days, but the difficulty of keeping on the trail was too great.

They were very careful to leave as little trail as possible. She said she frequently broke limbs of bushes, until the Indians noticed it and made her quit. When they left the house, they went up the side of a hill, in view of the house, and stopped and sat down on a log, staying some time, and fixed her and the children for traveling. They made her pull off her shoes and put on moccasins, on her and the two oldest children. She was in three months of having an infant.

When they got all fixed, one of the Indians, who spoke good English turned to her and said it was the Great Spirit that put her in their hands. She told him she knew it; but the thought passed through her mind that that same Great Spirit was able to take her out of their hands.

When they started, she had the child of two years to carry. The little boy gave out after traveling several days. Two of the Indians stopped behind with him; when they came up, he was not with them, and she saw him no more. After traveling several days, going up very high and steep mountains, she fell and was not able to get up. The Indians called to her to come along, but she lay still. One of them came, broke a switch and whipped her severely. She said she never felt it. While he was whipping her, she turned head and looked at him; he instantly drew his tomahawk. She turned her face from him and waited to receive the blow, but he did not strike. She made the exertion and got up and went to the other Indians. They took the child from her, set her on a log, and sat on each side of it, and appeared to be holding council, whether to kill it or not. After talking together some time, they asked if the child would have black eyes. She told them it would. One of them remarked her hair was very black. They immediately decided. One of them that had the saddle fixed it on your grandmother’s back, so that it gave her the use of her arms, which was a great relief to her. He set the child on top of his pack, which she said was a heavy one, and carried it to the towns.

In two days, they got home. He gave the child to one of his sisters who had lost a little one, and she saw it no more until it was given up about six months after. When it was taken from her it spoke English remarkably well for one of its years, and when she next saw it, it could not speak a word of English, but spoke Indian well. Nothing very material transpired until they got to the Indian town. They went through the mountains to Kenawah, where they had left their canoes, and went by water most of the way thereafter.

Soon after getting to the Indian’s home she was adopted into the family of King Beaver and was treated as one of them. She was, for a large portion of the time she was with them, at Zanesville. When the time arrived for her to be confined, they would not let her stay in the town, but sent her to the woods, the squaws attended her and carried her food. Her infant was born July 25, 1764.

The fall after, an army was sent against the Indians, commanded by General Boquette (I think his name is spelled). The Indians were alarmed and agreed to make peace and bring in all the person they held as captives, when upwards of two hundred persons were given up, and among them your grandmother, her infant three months old and the one two years old, the oldest having taken sick and died during the summer.

Your grandfather was with the army when the little girl was given up. Your grandmother knew her immediately, but he could not recognize her, and was in great uneasiness, until her mother asked him if he did not recollect having bled her in the foot. He said he did and stripped off her moccasin. There was the mark. The Great Spirit was kind to her and delivered her out of their hands in just six months from the time she was taken captive. They returned to Augusta County, from where she was taken, and remained there until 1789, and then moved here, where they lived until her death.

I have given you an account of your grandmother’s history. Perhaps all you wish to know. You know how I disliked writing. I did not think it would make such a long story, I intended to copy it when I began,, but for fear you should want it, I will send it as it is; perhaps you can read and understand it. Let me hear from you shortly and tell me if it will do.

Your affectionate parent,

John Kinkead

The annals of Augusta County substantiate this letter and also its contents is related in brief in Boquet’s Exposition against the Ohio Indians in 1764 page 78.

As you have heard, William Kincaid volunteered in Colonel Boquet’s expedition and was rewarded by being reunited with his wife and children. He must have had his doubts as to the safety of his former abode or else he was better off and decided to get nearer to civilization for in 1765 he bought from Samuel Hodge a tract of land on the Great Calf Pasture River where he resided until he came to Kentucky. (The old house still stands in a fine state of preservation.) And there he resided unmolested until 1789. He served as lieutenant and Adjutant, later as Captain in the Revolution. Records show that he marched in command of a company from Staunton in March 1777 to a block house on the west fork of the Monongahela River. Again in 1780 her served as captain of Militia and was allowed certificates for service in land grants in January 1780, and again February 15, 1780.

It was about the time of the Revolution that the spelling of the name was changed from Kincaid to Kinkead. Various reasons have been given for the change, but I have always thought that the deplorable weakness in that regard in his descendants may have come from him and account for it.

In 1789 there was quite a movement from Augusta County to Kentucky. The laws of the State of Virginia, concerning the domination of the Episcopal Church sat heavily on the consciences of the Scotch-Presbyterians and they resented the many inconveniences they entailed, so a number of them moved together to Woodford County, Kentucky, built a church and made their lives around it, and called it Pisgah.

William Kinkead and his wife bought a lovely place known as Cane Spring and lived there the remaining of their days leaving it to their son John Kinkead when they died, he on May 30, 1820, and Eleanor Guy Kinkead on October 9, 1825. They both lie buried in Pisgah churchyard.

Miss Bradley: ‘Pardon me if I add a bit of personal history. The little Isabella Kinkead of whom Mrs. Walton has just told you; who was stolen by the Indians; whose life was spared because of her very black hair; who was adopted by King Beaver; later brought in with the prisoners after Boquet’s treaty and restored to her family; grew to young woman hood and married Andrew Hamilton; this little Isabella was the great-grandmother of my own precious mother and the one for whom she was named. My mother not only inherited the name Isabella, but also the very black hair that saved the life of the first little Isabella and caused her to be adopted by King Beaver.’

‘Bancroft says, “The arrival of the lost ones formed the loveliest scene ever witnessed in the wilderness. Mothers recognized their lost babies; sisters and brothers, scarcely able to recover the accent of their native tongue, learned to know that they were children of the same parents.”’

Categories: Family Stories

I was speechless when I read this. How the family was separated and reunited – they were very strong people. Thank you for this narrative.

This is a wonderful piece of history. I live in Woodford County and am interested in the Kinkead family just as local history. Thank you!

So do any of the Kincaids, Kincade, Kinkead’s actually have Native American lines,DNA, children?? This has long been the story in my family, but I cannot track down a link. Here is a brief rundown of my line…. Celestia Jane Kincade (Kincade is how we spelled it) Father: Nathaniel Kincade and his father Edward Francis Kincade. Nathaniel’s family definitely look like they had Indian genes. Any help you could provide me will be very much appreciated. Thank-you so much.

I don’t think so. The children who were with their mother were too young.

I am working on my family tree and my Kincaid line goes to a James Kincaid born 1767 in Bath Virginia. He was married to Margaret Wyatt. His parents keep popping up as William Kinkead and Eleanor Gay (Guy). His name was even listed as James George Gay Kincaid. I notice in most articles online that they do not have a child born this year nor one named James. I also notice on William Kinkead’s grave, the plac. does not list a James as one of their children. However, I have found that on many other trees on Ancestry.com, people have James listed with the same parents. Can anyone confirm if Eleanor and William did have a son named James?

We are of similar lineage, because mine also leads to this “James George Kincaid” who does not seem to exist. I did see a website mention that Captain William Kincaid had 6 sons but as you see on the stone, only 5 are listed. So I am stuck in the same place you are. Did you ever find your answer on this? I would love to know!